How can you make a solid, accurate record of an ancient monument for the archaeological record, whilst also making an accessible digital experience with novel ways to view the site highlighting its construction? We think that we’ve cracked it.

Penwith Landscape Partnership asked us to capture 3D scans of four monuments as part of the Ancient Penwith strand of the project. It was critical that these were accurate so that they could be used for future condition monitoring purposes. At the same time, some of the sites are reasonably difficult to access because of their remote location, sometimes on private property, rough ground, and difficult to access for anyone who needs mobility assistance. This was also an opportunity for the archaeological data to be repurposed into 3D models which can be explored on all manner of devices via the Sketchfab platform.

Using Augmented Reality apps such as the Sketchfab app, you can even stand underneath Lanyon Quoit from the comfort of your own home to look under the capstone or beam yourself into the middle of the sun-dappled Madron Baptistry and have a look around.

We have completed all four of the sites now –

- Lanyon Quoit, the remains of a neolithic tomb

- Medieval Madron Baptistry (also known as Madron Well Chapel),

- Bosporthennis Beehive Hut (Romano-British building)

- Tregeseal Entrance Grave (neolithic / Bronze Age burial monument).

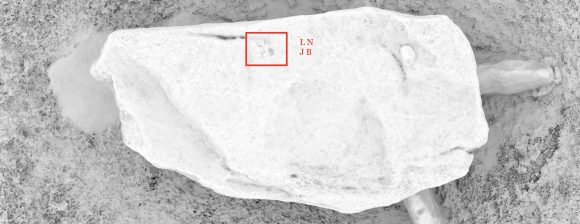

The outputs from these 3D scans represent our philosophy well — curating is half knowledge generation, half communication. They provide an accurate record of the present condition of the structures as they stand today which facilitate study and learning. We can use this data to study their surfaces and look for details that are difficult to spot with the human eye during a site visit, such as inscriptions, tool marks, decorations, damage, and much more. The data can be used in the future as a comparator to check for (and quantify) damage or erosion.

Using Augmented Reality apps such as the Sketchfab app, you can even stand underneath Lanyon Quoit from the comfort of your own home to look under the capstone or beam yourself into the middle of the sun-dappled Madron Baptistry and have a look around. Bosporthennis Beehive Hut is in the middle of the moor and was the most difficult to locate – we can now crawl through the small doorways, peer into the ‘cupboard’ and float above the monument to see the layout of the building and its later additions.

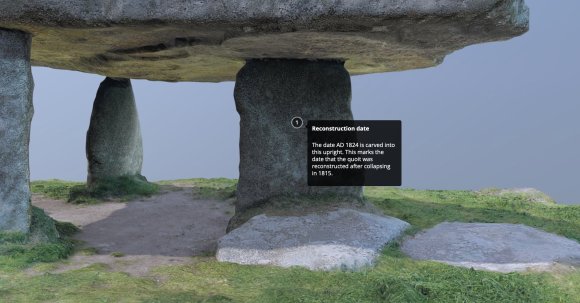

Annotations on the 3D model allow us to highlight elements and attach notes to them. We can point out important details and provide a rich experience not possible in a physical visit.

Visualising the unseen

One of the specifications for this project was to provide an alternative to the visually-pleasing photo-real 3D views. A way for people to be able to appreciate how the monuments were constructed. After some experimentation with transparency, we opted to go ‘lo-fi’ and use the point clouds – our giant 3D dot-to-dot – to do this. By not using any ‘solid’ faces in the model and reducing the number of points visible (200 million measurements is beyond many computers and most portable devices), we could achieve this interesting alternative.

In this example, looking at Lanyon Quoit from above, we can clearly see the alignment of the upright supporting stones.

Point clouds aren’t new – they’ve been around since the earliest beginnings of 3D scanning in the 1980s, but they aren’t used very often for public display as they can be difficult to interpret. We thinned the dense cloud of 3D dots, made the dots larger, and coloured them with their appropriate counterpart from the real world. We think that this method provides a useful alternative to the traditional approach of photorealism.

As you can see above, the point cloud of Madron Baptistry allows you to see the way the font in the lower right corner goes below ground. Exploring the model on Sketchfab you can see that the font ‘flares’ outwards and the base is sloping to keep the water in. All from an angle impossible in reality.

3D scanning can sometimes be a lengthy process. But with views like this, we weren’t complaining!

Explore more of the ancient Penwith landscape

Visit the Penwith Landscape Partnership channel on Sketchfab to explore the 3D models.